Soon to be finalized Debt-Equity regulations promulgated under Section 385 of the tax code will restrict the ability of American businesses to compete overseas and make routine investment and financing decisions. For decades, businesses have structured themselves around existing rules that differentiated the tax and legal treatment of debt and equity.

Now, these new regulations will empower the IRS – an agency that has become increasingly dysfunctional and politicized over the past eight years – with the authority to enforce confusing and complex new rules on American businesses. Despite the objections of Democrats, Republicans, and former Treasury officials, President Obama is set to unilaterally rush through these new rules in the twilight of his presidency, with little thought to how they will affect businesses.

As examined in a report by PricewaterhouseCoopers, Section 385 regulations will impact internal business transactions related to both inbound (foreign business operating in the U.S.) and outbound (U.S. businesses operating overseas) transactions.

The new rules will give the IRS extensive power over common transactions used by businesses to transfer assets across subsidiaries, including transactions used to financing the construction of a new factory in the U.S. by shifting cash across subsidiaries through a loan, or any routine transferring of cash across subsidiaries for finance purposes. Under the proposed rules, IRS bureaucrats have near unlimited authority to reclassify transactions as they see fit.

As noted by PwC, Section 385 regulations will increase the costs of transactions in a way that is comparable to hiking the corporate income tax rate. In turn, this will result in less money invested in the economy, slow the already stagnant U.S. economic growth, and further encumber the creation of new jobs.

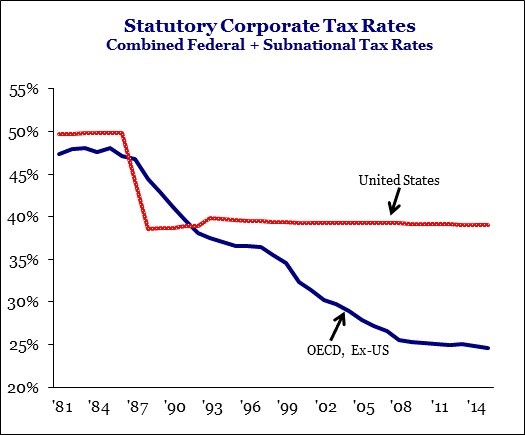

Already, American businesses are struggling to compete with the rest of the world because of our out-of-date, overly complex tax code. As shown in the chart below, America’s corporate income tax rate is close to 15 percent higher than the average in the developed world. The tax rate has barely changed since tax reform was passed 30 years ago in 1986. At the time, we lowered our rate to 39 percent – below the developed average of 44 percent. Since then, other countries have cut their rates aggressively, yet U.S. lawmakers have failed to do the same for our code.

Chart by Strategas Research Partners using Tax Foundation and OECD data

Our failure to lower our corporate rate to a competitive level and to modernize the system of international taxation has resulted in close to 50 American businesses leaving the country through an inversion in the past decade, according to data compiled by Democrats on the Ways and Means Committee. America has also lost an additional $179 billion worth of assets through acquisitions by foreign competitors, according to a report by Ernst and Young.

While there is a clear need for pro-growth tax reform, the proposed regulations will take the tax code in the other direction. The regulations will increase compliance costs and the cost of capital, making new investment more difficult and make harder for American businesses to compete with foreign competitors.