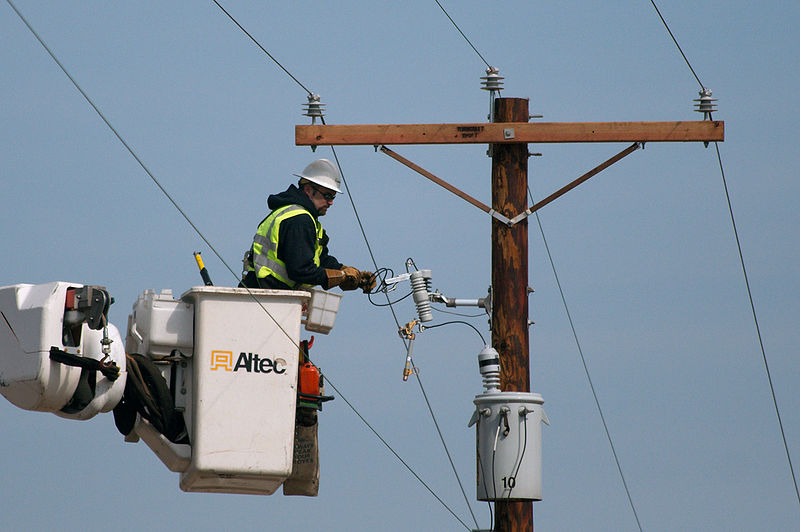

"Utility Worker" by Dori is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Utility_worker_4460.jpg

"Utility Worker" by Dori is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Utility_worker_4460.jpg

Over the past two years, lawmakers in various state capitals have enacted a new reform that will make occupational licensing requirements less of a barrier to employment. This new reform is known as universal license recognition (ULR). Arizona began this reform movement when it passed its ULR law in 2019. As of now, at least sixteen states have enacted it, the most recent being Mississippi in March (while four of these 16 laws had been on the books prior to 2019, this reform movement took off in earnest after the passage of the Arizona bill in 2019).

What are ULR laws? They are laws by which states recognize occupational licenses granted by other states. This means that if a worker in a licensed occupation moves to a new state that has passed universal recognition legislation, they can get to work right away. This gives workers greater flexibility and makes states with a ULR law more attractive to new residents.

ULR laws in various states tend to be similar, but not identical. According to Iris Hentze at the National Conference of State Legislatures, two of the most common requirements for recognition are “being licensed and in good standing with your home licensing board” and that the applicants “pay applicable fees and…undergo background checks.” While workers will need to eventually get a new license for the state they’ve moved to, in the 16 states with ULR laws “the process is shorter for licensed workers than it is for those seeking a license for the first time.”

One of the most significant differences between different ULR laws is whether they require “substantial equivalence” or “scope of practice” for recognition. According to Hentze at NCSL, states using “substantial equivalence” require that “that the license an applicant holds in his or her home jurisdiction be substantially equivalent to or exceed its own requirements” to have their license recognized in their new state of residence.

States using “scope of practice” on the other hand require the applicant to be “currently licensed or certified by another state to work in an occupation with a similar scope of practice”. According to the America Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), scope of practice is “a more direct comparison of whether a license is to perform the same day-to-day duties of the job itself.”

According to the Goldwater Institute, since “Arizona became the first state to enact universal recognition,” it has so far helped 3,000 professionals get to work in Arizona.

The push for universal license recognition was further spurred on when the COVID-19 pandemic showed how licensing requirements stifle worker mobility, particularly when additional healthcare workers were needed in some states more than others. According to ALEC, to meet demand “states like New York…issued temporary executive orders recognizing licenses for out-of-state healthcare workers.”

Since then, several more states have passed Universal Recognition laws, bringing the total to sixteen. Lawmakers in other states have introduced ULR that did not pass in 2021, but can be considered in future legislative session. According to the Goldwater Institute’s Heather Curry, “this session, more than 15 states have introduced legislation to extend out-of-state license recognition to skilled professionals.”

In a few short years, we’ve gone from zero to 16 states with ULR laws, four of them enacted in 2021 alone, with still more debating similar measures. This idea is catching on, as more and more states realize that letting workers do their jobs with minimal hindrance brings plenty of benefits and few, if any, costs.