Ways and Means Chairman Richie Neal (D-Mass) and Senate Finance Ranking Member Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) have recently released statements opposed to indexing capital gains taxes to inflation.

Neal and Wyden allege that indexing is a tax cut for “the rich,” that the policy will blow up the deficit and that executive action would be illegal.

Is Indexing an Irresponsible Tax Cut For The Rich? No.

Both Democrats allege that this is another tax cut for “the rich” following enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. First, as noted by the Joint Economic Committee, the TCJA actually made the tax code more progressive. Millionaires saw the share of federal taxes they pay go up (from 19.3% to 19.8%), while those making less than $50,000 per year saw their share of federal taxes go down (from 4.4% to 4.1%).Second, at worst indexing capital gains would reduce the share of the federal tax burden of the rich by a very minor amount. Democrats say that indexing capital gains would benefit the rich citing the Penn-Wharton Budget Model which said that 86 percent of the benefits follow to the top 1 percent of taxpayers.

However, that same study shows that the top 0.1 percent see their share of federal tax burden drop from 13.6% to just 13.5% and the 99 to 99.9 percent percentile see their share drop from 15% to 14.9%. In that context, it’s hardly a giant tax cut for the rich.

It is also important to note that taxpayers in the 0-20, 20-40, and 40-60 percentiles see no change in their share of federal tax burden from indexing capital gains to inflation.

However, this line of thinking also misses the point. Proponents of cutting the capital gains tax support this policy because it is a tax on investment and productivity. As noted below, reducing the tax will increase economic growth and efficiency.

Does this blow up the deficit? No.

The Penn-Wharton Budget Model estimates this proposal will cost $102 billion over ten years.This estimate should be considered the ceiling as it does not account for economic feedback. As the report notes: “This 10-year cost estimate of $102 billion ignores potential behavioral responses by investors.”

Even ignoring economic feedback, this $102 billion cost is a drop in the bucket compared to the policies pursued by the left. House Democrats just pushed a budget deal that increased spending by $324 billion over two years. If the Democrats had their way, this deal would have had no offsets. Speaker Pelosi even reportedly rejected a proposal from the White House to offset $150 billion of this increased spending.

Putting this hypocrisy aside, it is important to note that reductions in the capital gains tax have increased revenue in the short term.

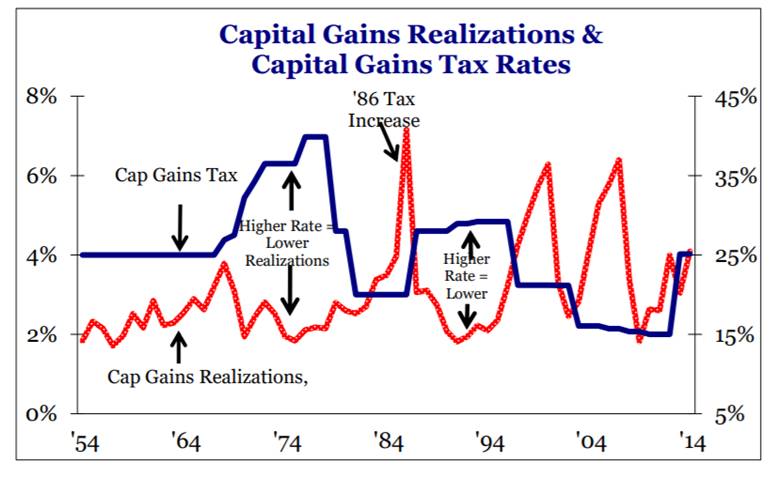

When tax rates are high, investors realize fewer gains. Conversely, when tax rates are lowered, investors realize their gains. In turn, this tax reduction triggers increased revenue to the federal government.

For example, capital gains tax cuts in 1997 and 2003 saw higher than projected revenues as noted in this document:

- In 1997, Congress cut the capital gains tax rate from 28 to 20 percent. Revenue estimators expected to collect $285bn of capital gains tax revenue for fiscal years 1997-2000. However, tax revenues came in at $374bn, 31 percent higher than revenue estimators suggested.

- As part of a larger tax bill in 2003, the capital gains tax rate was reduced from 20 to 15 percent. In 2003, JCT/CBO anticipated the government would collect $327bn of cap gains tax revenue over the 5 year cap gains tax cut. However, the government collected $537bn.

Indexing Capital Gains Will Have Significant Economic Benefits

Lower capital gains tax rates increase the after-tax rate of return on assets and push asset values higher. As asset values increase, there are more gains to be taxed. In nearly every case save for the 1981 recession, lower tax rates have translated into higher stock prices. Only in one instance, 2013, did stocks increase after the capital gains tax rate was raised and this was because monetary policy stimulus dwarfed the impact of the capital gains tax increase.

This would directly benefit the 54 percent of Americans that own stocks. By increasing asset values, this policy would also benefit the 55 million workers that own a 401k.

Over the longer term, a capital gains tax cut spurs the growth of new businesses, increases the wages of workers, enhances consumer purchasing power, and grows the economy at large, resulting in more overall gains to be taxed.

In addition, a significant portion of an asset is inflation. In fact, in some cases, inflation makes up the entire gain and the taxpayer actual has a loss when inflation is accounted for.

A taxpayer that purchases one share of Coca-Cola stock in 1998 would have paid $32.38 per share. Today, that share would be worth $48.13 with a gain of $15.76 and a tax liability of $3.75.

However, because of inflation, the value of a dollar in 1998 is worth $1.56. The inflation adjusted value of the stock is therefore $50.50 and the taxpayer has an inflation adjusted loss of $2.38.

Top Democrats used to agree that indexing capital gains to inflation was good for economic growth. In a speech on the House floor in 1992, then-Congressman and current Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) said: “If we really want to increase growth, there are proposals that we can do. I would be for indexing all capital gains and savings and borrowing.”

There is Strong Legal Precedent for Administrative Action

It is important to note that the IRS already makes inflation adjustments for over 60 tax provisions every year including adjusting individual income tax brackets, the standard deduction, and the Earned Income Tax Credit.

In addition, the authority to index capital gains taxes is based on existing legal precedent as outlined in legal memos (see here and here). According to these studies the cost basis of an asset when calculating the capital gains tax does not necessarily mean historical cost.

For instance, as noted in the 2010 Memo by Charles Cooper and Vincent Colatriano, the Supreme Court ruled that cost is ambiguous in Verizon Communications v. FCC (2002). As Cooper and Colatriano note, this eliminates the premise of a 1992 legal memo stating that the executive does not have legal authority:

“The Court unambiguously and forcefully rejected the notion that the term cost, either as a matter of common usage or as an economic term of art, unambiguously means only the historical price actually paid for an asset. The dictionary driven ‘plain meaning’ argument did not attract a single vote. Thus, the Court’s decision wholly eliminates the fundamental premise of the OLC’s dictionary driven ‘plain meaning’ analysis in its 1992 opinion.”

An agency is prohibited from changing statutory language and cannot adopt an interpretation of language that is prohibited in statute. However, the Supreme Court has also routinely ruled that courts should defer to an agency interpretation of the law that is “reasonable”. As noted in a memo by Peter Ferrara, this position has been reaffirmed as recently as several weeks ago when the Supreme Court ruled in Kisor v. Wilkie (2019).